[059] Bucephala clangula, Goldeneye

Introduction

Bucephala Clangula, the Goldeneye, is a diving duck usually only seen in Britain as a relatively rare Winter visitor. It is more strictly known as the Common Goldeneye.

Taxonomy

Kingdom – Animals

Phylum – Chordates

Class – Aves (Birds)

Order – Anseriformes

Family – Anatidae

Subfamily – Merginae

Genus – Bucephala

Scientific Name – Bucephala clangula

Note

There are three species in Bucephala. Two of these are quite similar – the Common Goldeneye and Barrow’s Goldeneye, which has a more Western distribution. The third one is quite different. It is the Bufflehead, with an appearance from which ‘Bucephala’ is derived.

There was a time when the Bufflehead was the only species in Bucephala. The Goldeneyes were placed in Clangula, while the Long-tailed Duck was in the genus Harelda. Now the Long-tailed Duck has been moved to Clangula and the Goldeneyes have become Bucephala.

It is still not universally agreed that the three species should stay together. The Goldeneyes may be moved out again – but they can no longer go to Clangula; they would have to go to a new genus!

Name

The eyes are small but the yellow ring round them is a clear identification feature.

Both parts of Bucephala clangula are really associated with other ducks, as noted above.

Description

The most noticeable feature of the male Goldeneye is not his eye. It’s the white circle below the eye. Apart from this, his head is dark green and the back is black. The rest of his body is white with a black and white striped effect at the sides.

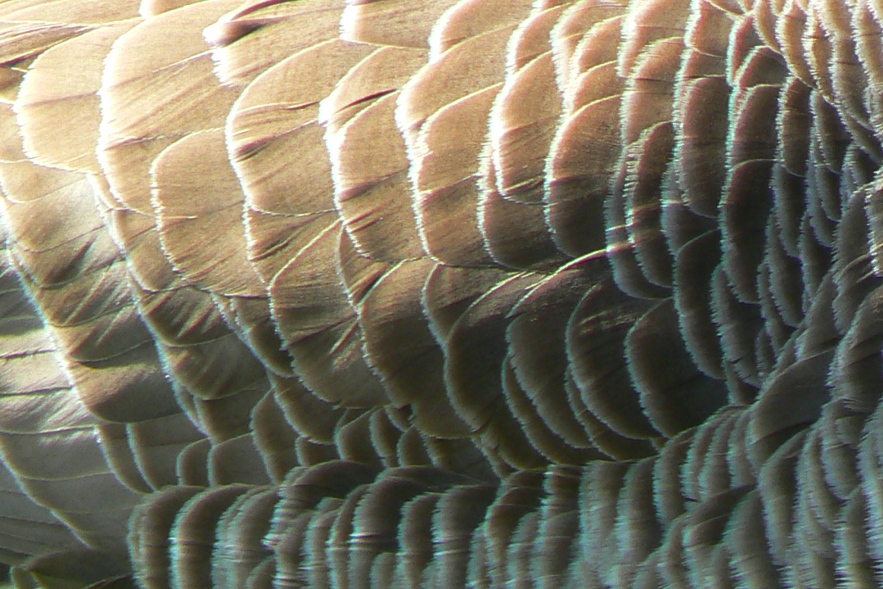

The female has a dark brown head without the white circle. Her body is dark on top with a more gradual mottled change to lighter colours underneath.

I think this next picture is a first winter male, or possible an eclipse form.

Most resident birds nest in holes in trees near to lakes. Most of the Scottish population make use of nest-boxes provided for them. They are diving birds and eat aquatic insects, crustaceans and molluscs.

They seem to use their flat tails to help them dive.

Habitat and use

Most Goldeneye spent their summer in the far North. They winter in the far East, the US and the UK. There is a very small resident population in Scotland

Other Notes

This is a relatively rare visitor to the South of England. The lakes of the Cotswold Water Park generally support a few birds.

You have to be careful sometimes when doing Internet searches. Make sure you exclude James Bond and the horse belonging to Alexander the Great.

And not every bird with a golden eye is a Goldeneye.

You will, of course, recognize [047] the Tufted Duck.

See also

Goldeneye tend to appear with another rare Winter visitor, [228] the Goosander.